What a Decade of Data Tells Us About Canada’s Automotive Future

We are halfway through one of the most consequential decades in the history of the automotive industry in Canada, in North America, and globally. This decade is marked by the widespread adoption of electrified and connected vehicle technologies, dramatic shifts in government policies and priorities, and the emergence of a number of new vehicle and propulsion system manufacturers.

These changes have had profound effects on the automotive industry in Canada. This bulletin presents 10 years of data related to Canadian passenger vehicle and light-duty truck production, employment, and labour productivity. In doing so, it illustrates just how much has changed over this time.

In this context, the bulletin also identifies three policy concepts that we recommend the federal government adopt in its much-anticipated automotive strategy. Each of these concepts, if properly incorporated into the strategy, would help to maintain and grow a globally competitive automotive industry in Canada.

Vehicle Production

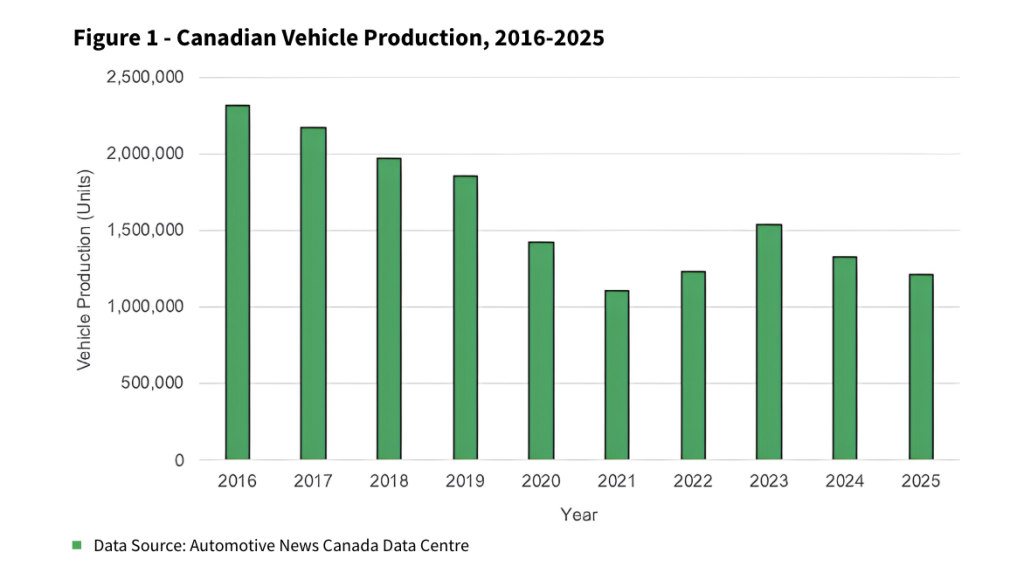

The most dramatic changes to the automotive industry in Canada have occurred in vehicle assembly plants. Five automakers operate passenger vehicle and light-duty truck assembly plants in Canada: Ford, General Motors, Honda, Stellantis (formerly FCA), and Toyota. Together, these automakers assembled 2.3 million vehicles in 2016. In 2025, they assembled 1.2 million vehicles (Figure 1).

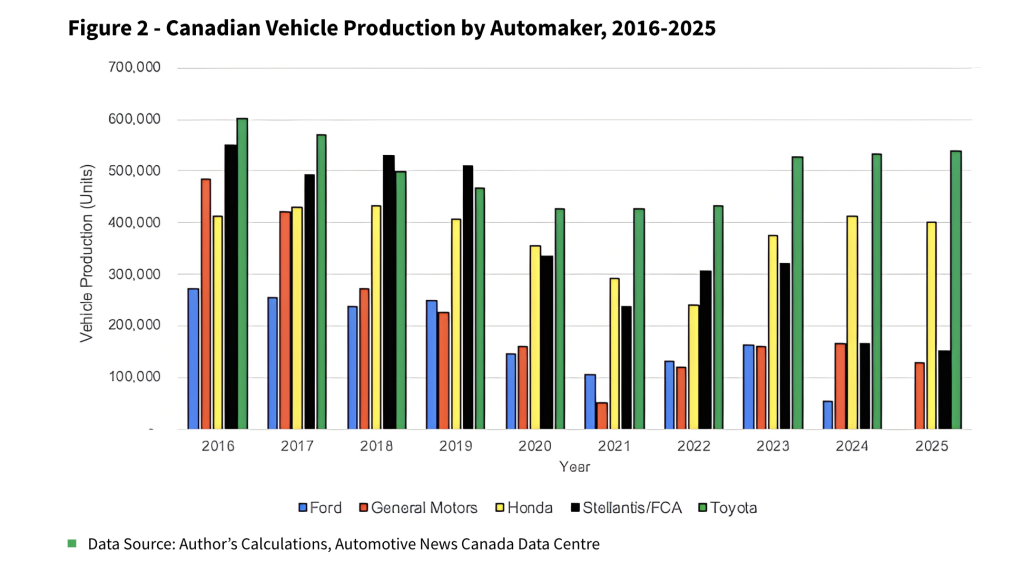

These decreases in vehicle production were not uniform across the five automakers. In 2016, four companies–FCA, General Motors, Honda, and Toyota–regularly assembled more than 400,000 vehicles in Canada annually. By 2025, only Honda and Toyota claimed that distinction. In fact, Honda and Toyota each assembled more vehicles in Canada than did Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis combined in 2024 and 2025 (Figure 2). As Figure 2 illustrates, the proportion of vehicles produced by US-based automakers fell from 56 per cent in 2016 to 23 per cent in 2025, while the proportion produced by Japan-based automakers increased from 44 per cent to 77 per cent. The shift in the proportion of vehicles produced by Japan-based companies when compared to US-based companies over the past decade is the most significant change in the structure of the automotive industry in Canada since the mid-1980s.

Assembly Plant Employment

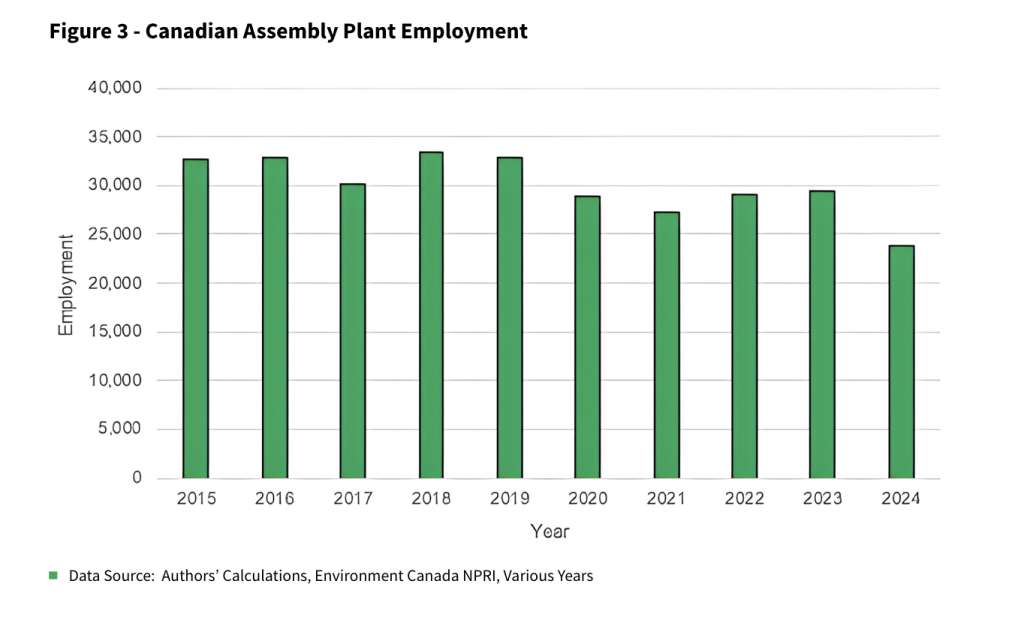

The number of persons employed in vehicle assembly plants decreased as well amid the drop in production at assembly plants operated by US-based automakers. In 2015, passenger vehicle and light-duty truck assembly plants employed 32,700 people. In 2024 (the most recent year for which complete employment data is available), they employed 23,732 people (Figure 3). Today, that number is slightly lower following layoffs at General Motors’ two Canadian assembly plants. There is hope, however, that the number of people employed in assembly plants operated by US-based automakers will grow over the next year following the addition of a third shift at Stellantis’ Windsor Assembly Plant and the restart of production at Ford’s Oakville Assembly Plant.

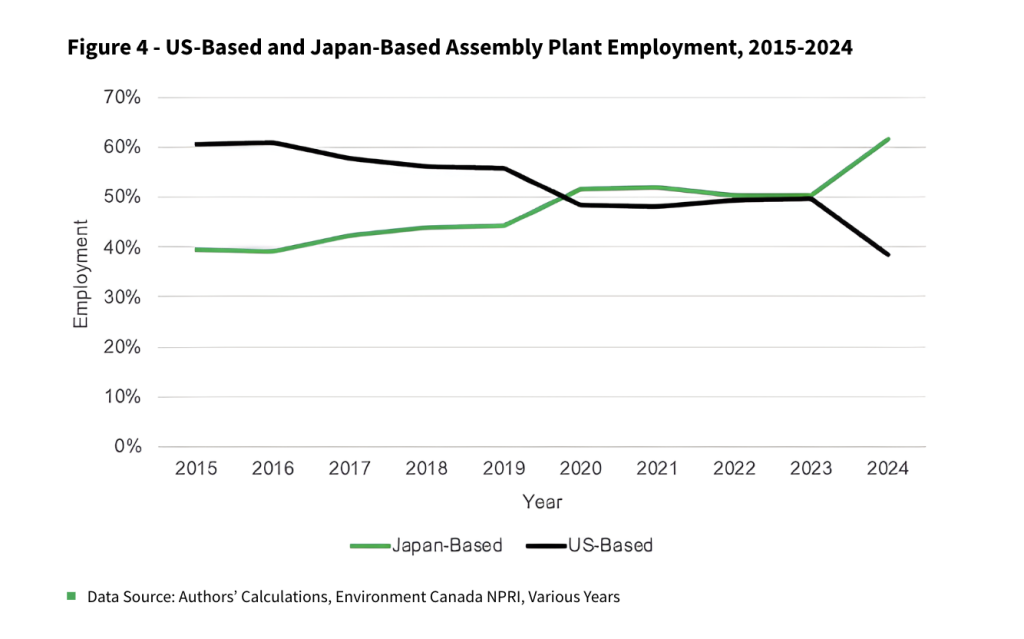

The proportion of persons employed in US-based automaker assembly plants when compared to Japan-based automaker assembly plants has inverted since 2015. In 2015, US-based automakers accounted for 60 percent of all assembly plant employment. That number fell to 48 per cent in 2020 and to 38 per cent in 2024 (Figure 4). This change has caused a precipitous decrease in union density in Canadian passenger vehicle and light-duty truck assembly plants, which is now approximately 33 per cent (in automotive parts manufacturing union density is less than 20 per cent).

Stable production and employment at Japan-based automakers’ assembly plants amid decreased production and employment at US-based automakers’ assembly plants is no surprise to those who keep an eye on the automotive industry in Canada. What is perhaps surprising is the impact of these changes on labour productivity.

Labour Productivity

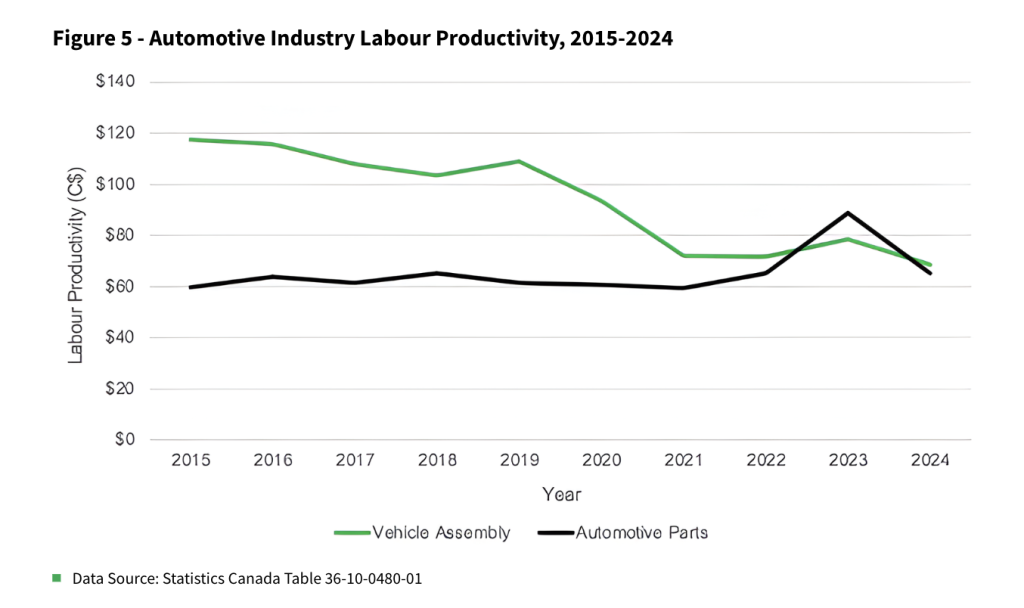

Slow rates of labour productivity growth are a growing concern for Canada’s economy. The automotive industry is no exception. In 2015, labour productivity in Canadian passenger vehicle and light-duty truck assembly plants was $118 an hour. In 2020, labour productivity was $95 an hour. This dip was not terribly surprising considering the circumstances surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2024 (the most recent year for which data is available), labour productivity fell to $69 an hour (Figure 5). In an environment where Canadian companies must prioritize improving competitiveness, this is a major concern.

The assembly plants operated by Japan-based automakers consistently produce more than 900,000 vehicles annually. Employment in these plants has been relatively constant since 2018. The vehicles that they produce today are of a higher value than those they produced 10 years ago (think 2026 Toyota RAV4 Hybrid vs. 2016 Toyota Corolla). Japan-based automakers’ Canadian facilities regularly receive JD Power awards for initial plant quality. No other automaker’s Canadian assembly plants have received such an award since 2013. Japan-based automakers are leading the way when it comes to labour productivity.

The problem lies in idle and under-utilized assembly plants operated by US-based automakers. Idle and under-utilized assembly plants are a drag on labour productivity. The frequent and often prolonged layoffs that the Canadian employees of US-based automakers must endure are similarly unproductive and disruptive to the lives of those who would prefer to be working. It is increasingly important to Canada’s economic well-being that large manufacturing facilities such as US-based automakers’ assembly plants do not sit mostly or completely empty for prolonged periods. Yet this is exactly what we have witnessed recently, where three of five assembly plants owned by US-based automakers sit idle, and another operates below capacity.

Automotive Parts Manufacturing

The automotive parts manufacturing industry has fared better than vehicle assembly, at least until recently. In 2015, Canadian automotive parts manufacturers employed about 71,000 people. In 2024, they employed 72,000 people. That number, however, has likely fallen since 2024 due to a series of plant closures and layoffs.

Productivity in the automotive parts manufacturing industry increased from $60 an hour in 2015 to $65 an hour in 2024. This is good news, not great news. Some of these increases are the result of companies making improvements in their existing facilities, which are increasingly necessary to compete with suppliers in the United States and Mexico. Some of the increases, however, are the result of inefficient automotive parts manufacturing facilities closing.

Conclusion

The automotive industry in Canada has changed. These changes are evident when we compare the current situation to either 2016, or to 2020 when US-based automakers committed billions of dollars worth of investments in EV manufacturing following collective bargaining, only to cancel or postpone those investments a few years later. In order to develop a strategy designed to support the industry moving forward, it is important to understand and accept these changes.

The Trillium Network welcomes the federal government’s automotive strategy, which is scheduled to be announced in February. We hope that its key pillars reflect the realities of the Canadian, North American, and global automotive industry as they are, not as they once were. In Canada, that reality is one where Japan-based automakers are leading the way, the role of US-based automakers is diminishing, and investments in emerging technologies are welcome.

Recommendations

While we anticipate that the federal government’s automotive strategy will be wide-ranging, we recommend that it incorporates three policy concepts:

- Leverage Canada’s buying power, found in its large market for passenger vehicles and light-duty trucks (1.9 million units in 2025), to secure further automotive manufacturing investment;

- Reward and incentivize automakers and automotive parts manufacturers that have consistently invested and grown their Canadian manufacturing footprint1; and

- Encourage the use of Canadian-made production technologies in vehicle assembly and automotive parts manufacturing facilities as a means to improve productivity and job quality.

1 Examples of companies that have grown or are in the process of growing their Canadian employment or manufacturing footprint over the past decade include Honda, Linamar, Multimatic, Toyota, and Volkswagen subsidiary PowerCo.