Engaging younger generations of the workforce is vital to the future of manufacturing in Ontario. This has proven challenging, however, for manufacturers, and for employers across all sectors of the economy. One of the reasons for this, we hypothesize, is that the earnings of younger generations have not kept pace with those of older generations of the workforce in Ontario.

To test this hypothesis we analyze earnings and employment data from the 1996, 2001, 2006, 2016, and 2021 censuses. We compare the average earnings of Ontarians by six age categories across these censuses, controlling for the proportion of the workforce that each age category represents over time. The result is a metric that illustrates the change in earnings by age over time. We refer to this as the generational earnings premium/discount delta.

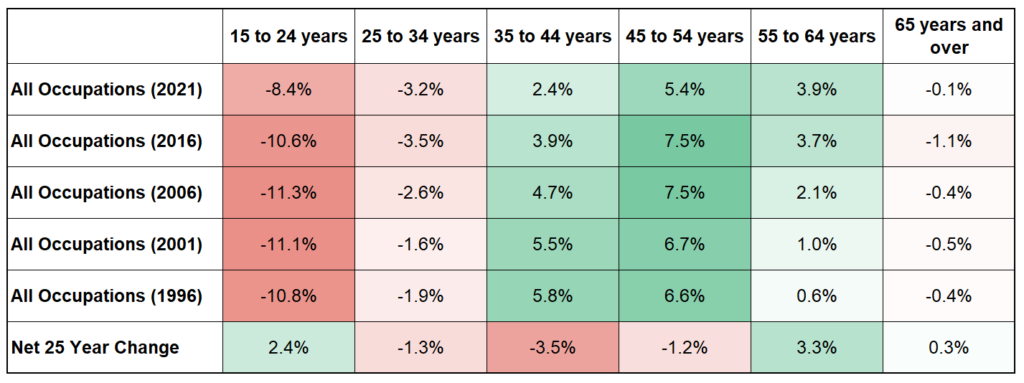

A positive number indicates the proportionally-controlled extent of the premium that employed persons in a particular age category earn on average over the average for all employed Ontarians. A negative number indicates a discount. These are displayed in the table below.

Trillium Network Generational Earnings Premium/Discount Delta

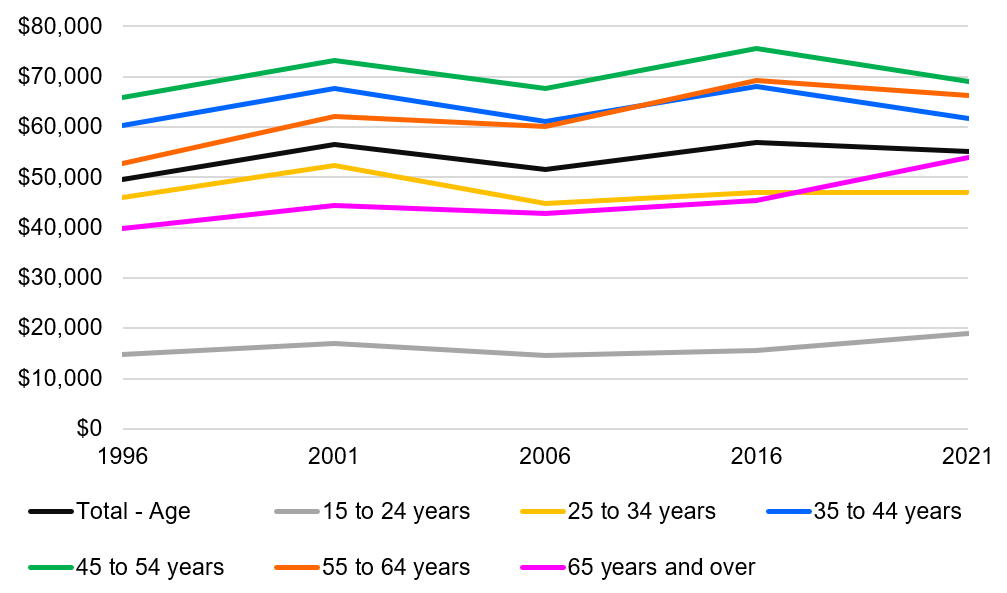

The good news is that, after controlling for inflation, Ontarians earned 11.2 per cent more on average in 2021 than they did in 1996. By this measure, Ontario is more affluent today than it was in the 1990s. The bad news is that, by the same measure, Ontarians earned 3.1 per cent less on average in 2021 than they did in 2016. Inflation and pandemic-related disruptions have taken a toll on the province (see the Figure below).

Inflation-Adjusted Average Earnings, 1996-2021

Similarly concerning is that the distribution of the increases in earnings has not been shared equally across generations over time. Rather, those gains have become increasingly concentrated among employed Ontarians above the age of 54. More specifically:

- Employed Ontarians over the age of 65 have experienced the largest increase in average earnings;

- Those aged 55 to 64 also saw substantial increases;

- The youngest category, those aged 16 to 24, shrank in the number of people working, but saw substantial growth in average earnings over the past five years, likely a result of increases to the minimum wage;

- Ontarians aged 25 to 44 saw only small increases in their average earnings at a time when the cost of living has increased substantially.

Employed persons aged 45 to 54 have long had the highest average earnings. Historically they were followed by those aged 35 to 44. Sometime between 2006 and 2016, however, persons aged 55 to 64 began to out-earn those aged 35 to 44. It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when this happened due to the unreliable 2011 census, but it is likely caused by a combination of demographics (an aging population) and legislative changes (the end of mandatory retirement). Whatever the cause, census data shows that in 1996 Ontarians aged 35 to 44 earned on average 14 per cent more than those aged 55 to 64. In 2021 they earned 7 per cent less than the older cohort.

In short, the generational earnings premium, which in Ontario long favoured those aged 35 to 54, has shifted to older generations of workers. This is concerning for several reasons.

First, it exacerbates already-historical labour shortages. Wages and salaries are the best recruitment and retention tool. When one generation watches another reap these benefits, seemingly at their expense, the motivation to engage, innovate, or even stick around diminishes considerably.

Second, when combined with the rising cost of living in Ontario, the shift in the earnings premium is likely behind much of the out-migration the province is witnessing. The generational earnings discount that Ontarians aged 25 to 44–who tend to be more mobile than older generations–now endure is chasing intelligent and educated people out of the province. It also changes the calculus for new Canadians, on whom so many employers rely, who may choose to migrate elsewhere in Canada. You’re welcome, Alberta (where those under the age of 35 are nominally and relatively better off than their counterparts in Ontario).

Third, it jeopardizes the ability of younger generations of Ontario to create wealth–with the exception of the independently wealthy and those who are lucky enough to rely on their family for financial support. Saving for retirement and building equity through the housing market is rapidly becoming a pipe dream for even the hardest working Ontarians in their 20s, 30s, and increasingly, 40s.

Fourth, this drop in younger generations’ relative earnings causes them to delay forming households and starting families. This has an important but seldom discussed effect on the labour market. The older parents are when they first have children means the more workforce experience they have when they take parental leave. This was less of a problem in the past, when parents, mostly mothers, took leave after having children beginning in their mid-20s (compared to their early 30s). Replacing a mid-career employee, even temporarily, is much more difficult than replacing an entry-level one.

Our analysis of the manufacturing sector, specifically, yielded similar results. Older generations are out-earning younger ones by a greater proportion than in the past. We observed one important difference, however. The number of persons working in manufacturing who are under the age of 45 has decreased considerably, in both nominal and proportional terms.

If manufacturers are seeking to gain an advantage over employers in other sectors they should consider how they compensate entry-level employees. Relatively high compensation for entry-level employees was something manufacturers were known for in the past and helped attract younger workers to the sector. This has changed as many adopted two-tier wage systems and extended grow-in periods for new hires following the recession of 2008-2009. Such compensation schemes seem increasingly at odds with an industry that, as we hear time and time again, is in dire need of younger generations to replace its aging workforce.

Let’s not get things twisted: lots of good comes with people working longer. This is especially true during a labour shortage. But from a broader societal standpoint, how much value does working longer create if it comes at the expense of younger generations, who face mounting challenges building equity through housing, investing in their retirement, and starting a family?

Key Takeaways

- Older generations are out-earning younger ones by a greater proportion than in the past.

- The shift in generational earnings have important implications on the labour market, interprovincial migration, and generational savings.

- If manufacturers are seeking to gain an advantage over employers in other sectors they should consider how they compensate entry-level employees.