Recent decisions by the Trump-led U.S. government to upend well-established trade agreements have led to widespread discussion about the potential benefits of localized supply chains.

To this effect, the Government of Ontario recently introduced legislation to encourage domestic consumption and reduce interprovincial barriers to trade. Recently-elected Prime Minister Mark Carney has also stated his intention to eliminate internal trade barriers as soon as Canada Day. That’s about seven weeks from now.

There are initial indications that Canadian consumers are at least open to making conscious decisions to increase purchases of domestically-made goods. Anecdotally, they appear to be already doing so. While these decisions limit consumers’ choice of certain products (e.g. vehicles), they have brought to light hundreds of options to increase the consumption of Canadian-made food and beverage products.

As trade discussions with the United States continue, the highly-integrated automotive industry continues to receive considerable attention (and rightfully so). The same goes for steel and aluminium, the first major industries to face new tariffs imposed by the Trump administration. The Canadian dairy industry and its provincially-administered supply management systems, long an irritant in trade negotiations between Canada and the U.S., also appear in the cross-hairs of negotiators south of the border.

The dairy product manufacturing industry offers a good example of an industry and supply chain that, through a legislated supply management system, is almost entirely contained within Canada, and often within individual provinces.1 Dairy product manufacturing illustrates both the economic benefits and the potential drawbacks of a domestically- or provincially-contained industry that is much less exposed to trade than other industries.

Dairy products are different from most goods manufactured in Ontario. They are perishable, tend not to age well, and generally don’t travel far. This is an important distinction when compared to non-perishable foodstuffs and other durable products, like vehicles, aluminum, and steel.

The dairy product manufacturing industry employs about 9,000 people in Ontario. The companies that employ these people produce fluid milk, butter, cheese, yogurt, ice cream, and other specialty dairy products. A large majority of companies use cow’s milk as their primary input. Virtually all of the raw milk used by Ontario producers comes from within Ontario. A small amount comes from Quebec. Some smaller producers use milk from other animals, such as goats and sheep.

Most of the dairy product manufacturing industry is located in southern Ontario. A few companies operate in northern Ontario communities such as Thunder Bay, Sudbury, and Kapuskasing. But most operate in the south, between London and the Quebec border. There is little dairy product manufacturing in the far southwest. The primary exception is one well-known producer in Windsor–Galati Cheese Company–whose products are a key ingredient in the style of pizza unique to that city.

Cooperatives, such as the larger Gay Lea Foods and Agropur, as well as a network of smaller organizations, play an important role in the industry. They represent dairy farmers and manufacturers. Other larger Canadian-headquartered companies, such as Chapman’s and Saputo, multi-nationals such as Unilever and Lactalis, and a network of smaller independent producers, all play an important role in the industry.

Ontario dairy product manufacturers tend to pay well. The average hourly compensation of dairy product manufacturing employees is around $65. This is considerably higher than the average for all Ontarians ($46) or for manufacturing employees ($54). Wages make up about 70 per cent of dairy product manufacturing employees’ compensation, and benefits the remainder.

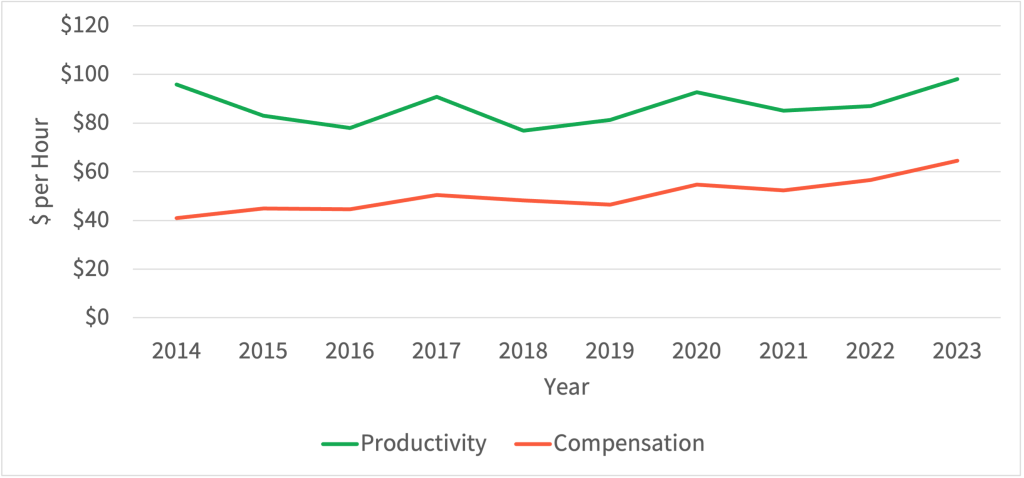

Productivity in Ontario’s dairy product manufacturing industry is similarly high. Hourly productivity in the industry is about $98. This is greater than the Ontario average ($62) or the manufacturing average ($74). In fact, it is greater even than the motor vehicle manufacturing industry ($79), whose productivity has decreased recently as the result of several U.S.-owned assembly plants being idled or operating at less than capacity since 2019. The growth of wages and productivity in Ontario’s dairy product manufacturing industry are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Ontario Dairy Product Manufacturing Productivity and Compensation

Sources: Author’s Calculations, Statistics Canada Table 36-10-0480-01

The economic multiplier benefits associated with dairy product manufacturing are very high. Based on the most recent data available, the dairy product manufacturing industry has a Type II jobs multiplier of 5.97. This means that every job in a dairy product manufacturing facility leads to 4.97 jobs elsewhere in the economy. As Table 1 illustrates, the multiplier associated with dairy product manufacturing is considerably higher than other important industries such as meat product manufacturing (4.77), bakeries (2.17), pharmaceutical products (2.43), steel mills (3.98), and motor vehicle manufacturing (3.97).2

Table 1 – Type II Jobs Multiplier, Select Industries

| Industry | Multiplier |

| Dairy Product Manufacturing | 5.97 |

| Meat Product Manufacturing | 4.77 |

| Iron and Steel Mills | 3.98 |

| Motor Vehicle Manufacturing | 3.97 |

| Medicine and Pharmaceutical Products | 2.43 |

| Bakeries and Tortilla Manufacturing | 2.17 |

Source: Statistics Canada Table 36-10-0013-01

The relatively high wages and productivity of dairy product manufacturers are the result of several factors. A stable supply of inputs (i.e. milk) and demand for dairy products is chief among them. This allows companies–producers and farmers alike–to make long-term investments in machinery and automation, leading to further productivity gains. High wages lead to substantial income tax payments and expenditures by dairy product manufacturing employees. This leads to relatively high levels of induced employment.

Importantly, Ontario manufacturers source nearly all of their inputs from within Canada (and a large proportion from within Ontario). This leads to high levels of employment on dairy farms and in businesses that support those farms. Every dairy product manufacturing job supports about one and a half jobs in agriculture. These include jobs in dairy farming and activities that support dairy farming. They also support a considerable number of jobs associated with getting those dairy products to market. For more details on economic multipliers, see this Trillium Network data bulletin.

Ontario’s consumer market for dairy products is about $8.7 billion annually. Ontario dairy product manufacturers supply about 60 per cent of that market. Quebec manufacturers supply another 26 per cent, and British Columbia manufacturers supply about five per cent. Shipments from the rest of Canada are negligible. Imports from the United States account for most of the remainder of the market, about eight or nine per cent.3 Processed cheese accounts for a majority of dairy product imports from the United States.

Ontario dairy product manufacturers produce just over $8 billion worth of product annually. Just under two-thirds of those products are sold in Ontario. Another 12 per cent are sold in Quebec, nine per cent in western Canada, and three per cent in Atlantic Canada. About nine per cent of dairy products manufactured in Ontario are exported, almost exclusively to the United States (Table 2).

Table 2 – Ontario Dairy Product Exports (C$ x 1,000), 2024

| Category | US | Rest of World |

| Fluid Milk | $409,287 | $14,474 |

| Butter, Cheese, Dry & Condensed Dairy Products | $298,877 | $65,228 |

| Ice Cream | $30,191 | $126 |

Source: ISED Trade Data Online

A recent CTV article, which is otherwise well-written, suggests that Canada is a major importer of U.S. dairy products. We offer an alternative perspective: not really. The more than $1 billion of dairy product imports from the U.S.–again, mostly processed cheese–sounds like a lot. But relative to the overall market, it’s not all that much.

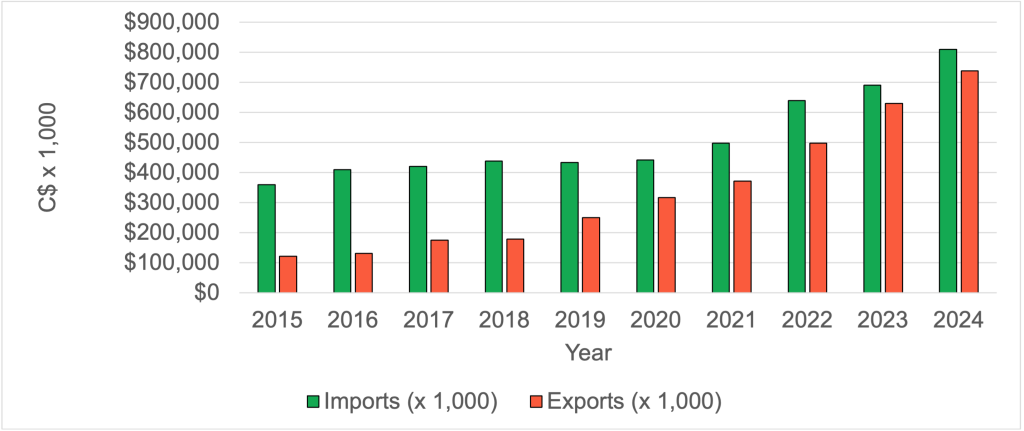

The author of the article does accurately note that dairy product imports from the U.S. have nearly doubled over the past decade. At the same time, dairy product exports from Ontario to the U.S. have increased sixfold, although they were negligible to begin with. Figure 2 illustrates Ontario dairy product trade with the United States over the past decade.

Figure 2 – Ontario Dairy Product Manufacturing Trade with US, 2015-2024

Source: ISED Trade Data Online

It is important to note that Ontario, and Canada, have a deficit in dairy product trade with the United States. By Trump’s recently-advanced (but misguided) logic, Ontario is subsidizing the U.S. dairy industry to the tune of $71 million annually!

Similarly, Ontario has a deficit in dairy product trade with the rest of the world of about $240 million. Most of this deficit is related to premium cheese products: Irish cheddar, French brie, and Queijo São Jorge from the Azores (if you can find it). This deficit has increased threefold since the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)– the agreement governing trade between Canada and the EU– entered into provisional application in 2017.

Have these relatively small trade deficits cratered Ontario’s dairy product manufacturing industry? The data in this bulletin suggests that they have not.

There are advantages to Ontario’s supply-managed dairy industry. The most obvious are related to its economic impact, as measured by both the quality and quantity of jobs. The methods of dairy farming engendered by the supply management system offer environmental benefits, reduce the risk of disease among dairy cow herds, and support community-oriented family farms at a time when other segments of agriculture that were once family-based have largely given up the ghost and been amalgamated into corporate-controlled entities.

Less obvious is that Ontario’s dairy industry offers a platform for food and agricultural innovation. I’m sure the good folks at the University of Guelph and its Guelph Food Innovation Centre (GFIC), which is widely heralded as a global ‘ice cream centre of excellence’, would agree.

There are also disadvantages. First, Ontario consumers pay more for milk and dairy products than Americans. Currently, and despite a recent spike in the price of milk in the United States, Ontario customers pay about C$1 more for four litres of milk than Americans. That premium has been as high as C$2 at some points in the past decade. In an age of unaffordability, this is a hard sell. Second, while the dairy product manufacturing industry is stable, there are limited growth opportunities. There may be opportunities to sell more to markets in western Canada, although these are limited by the relatively short shelf life of dairy products and competition from local producers, as well as those from Washington and Oregon. These limited growth opportunities are also related to the growing number of non-dairy substitutes available to Ontario consumers. Finally, Ontario’s supply-managed dairy industry persistently draws the ire of U.S. trade negotiators. While the effects of this on the economy are hard to quantify, it may be increasingly difficult to justify protecting the dairy industry at the expense of other, larger segments of the economy.

The case of the dairy product industry demonstrates the potential economic benefits and value associated with the localization of supply chains. It also demonstrates some of the challenges and drawbacks associated with localization. Understanding the nature and extent of both across the economy is imperative if we are to pursue a strategy designed to promote greater localization of supply chains.

It is also important to understand that individual industries and supply chains are distinct. What might work well in one industry–in this case, dairy products–may not work in another industry. Some industries and related supply chains may prove easier to localize than others. In this case, dairy products appear to lend well to such localization. The highly-specialized operations that make up the integrated cross-border supply chains of the automotive, steel, and aluminum industries will be much more difficult, if not impossible, to localize within the span of one or two election cycles.

Exploring opportunities for export diversification is also worthwhile. Like eliminating interprovincial trade barriers, exploring opportunities to expand trade relationships with democratically-governed countries outside of North America can help our economy in the short- and long-term.

That said, we should be careful not to over pursue these opportunities–and their uncertain and potentially limited benefits–at the expense of the most important task at hand: negotiating a modern, fair, and reciprocal trade agreement with our long-standing ally and trading partner, despite its ornery and exasperating head of state.

1 More information about Canada and Ontario’s supply management system for dairy (and other agricultural products) is available here and here.

2 Two notes on economic multipliers: 1) meat product manufacturers, especially poultry processors, also have high economic multiplier benefits due to local sourcing, 2) the economic multiplier associated with motor vehicle manufacturing is often exaggerated. Claims of economic multipliers as high as 10 are patently false. Even claims of multipliers as high as 6 or 7 are at best outdated or are based on analyses of the industry in the United States, where automakers source a greater proportion of higher-value powertrain systems and components domestically.

3 An undetermined but material amount of these products are imported by cross-border shoppers rather than producers, wholesalers, or retailers. This money-saving practice is common in border communities such as Niagara, Windsor, and Sarnia.